Evgeniy Maloletka

MARIUPOL

The bodies of the children all lie here, dumped into this narrow trench hastily dug into the frozen earth of Mariupol to the constant drumbeat of shelling.

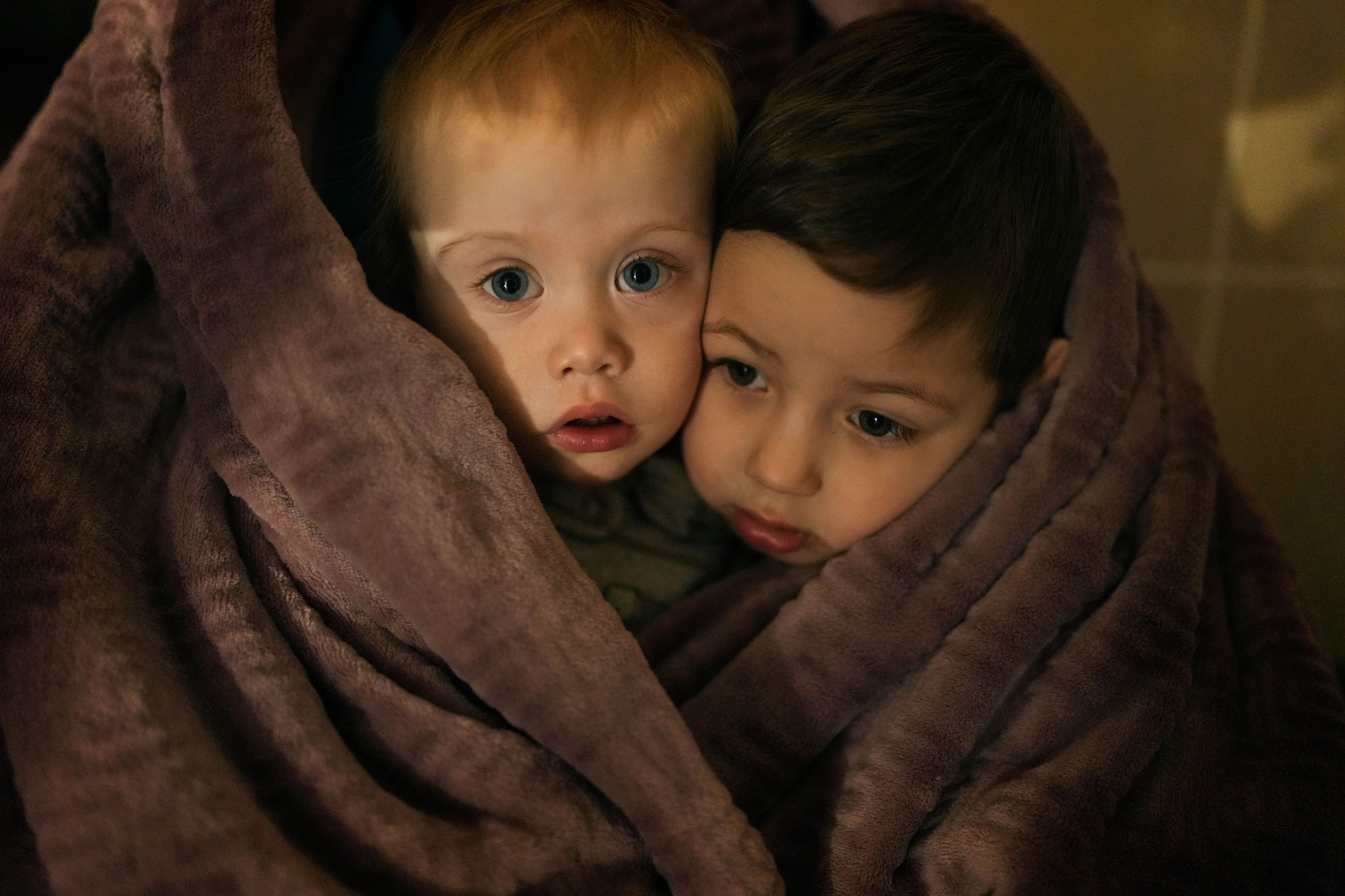

There’s 18-month-old Kirill, whose shrapnel wound to the head proved too much for his little toddler’s body. There’s 16-year-old Iliya, whose legs were blown up in an explosion during a soccer game at a school field. There’s the girl no older than 6 who wore the pajamas with cartoon unicorns, among the first of Mariupol’s children to die from a Russian shell.

They are stacked together with dozens of others in this mass grave inside the city. A man covered in a bright blue tarp, weighed down by stones at the crumbling curb. A woman wrapped in a red and gold bedsheet, her legs neatly bound at the ankles with a scrap of white fabric. Workers toss the bodies in as fast as they can, because the less time they spend in the open, the better their own chances of survival.

More bodies will come, from streets where they are everywhere and from the hospital basement where adults and children are laid out awaiting someone to pick them up. The youngest still has an umbilical stump attached.

Each airstrike and shell that relentlessly pounds Mariupol — about one a minute at times — drives home the curse of a geography that has put the city squarely in the path of Russia’s domination of Ukraine. This southern seaport of 430,000 has become a symbol of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s drive to crush democratic Ukraine — but also of a fierce resistance on the ground.

The surrounding roads are mined and the port blocked. Food is running out, and the Russians have stopped humanitarian attempts to bring it in. Electricity is mostly gone and water is sparse, with residents melting snow to drink. Some parents have even left their newborns at the hospital, perhaps hoping to give them a chance at life in the one place with decent electricity and water.

People burn scraps of furniture in makeshift grills to warm their hands in the freezing cold and cook what little food there still is. The grills themselves are built with the one thing in plentiful supply: bricks and shards of metal scattered in the streets from destroyed buildings.

A Ukrainian military radar and airfield were among the first targets of Russian artillery. Shelling and airstrikes could and did come at any moment, and people spent most of their time in shelters. Life was hardly normal, but it was livable.

By Feb. 27, that started to change, as an ambulance raced into a city hospital carrying a small motionless girl Evangelina, not yet 6. Her brown hair was pulled back off her pale face with a rubber band, and her pajama pants were bloodied by Russian shelling.

Her mother stood outside the ambulance, weeping.

As the doctors and nurses huddled around her, one gave her an injection. Another shocked her with a defibrillator. A doctor in blue scrubs, pumping oxygen into her, looked straight into the camera of journalists allowed inside and cursed.

“Show this to Putin,” he stormed with expletive-laced fury. “The eyes of this child and crying doctors.”

Mariupol city became a trap, where for more than 20 000 people have been killed.

Death were everywhere.

Evgeniy Maloletka – is a Ukrainian freelance photographer and filmmaker based in Kiev, Ukraine, originally from the city of Berdyansk, the Zaporizhya region in the easternUkraine. In 2015, he was selected to participate in the Eddie Adams Workshop in New York. He spent most of his time in eastern Ukraine working on assignment for The Associated Press. His work was published in numerous prominent media: TIME, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Der Spiegel, Newsweek, The Independent, El Pais, The Guardian, The Telegraph and others.